Siberian Huskies are known for their striking looks, boundless energy, and spirited personalities. These same traits, however, often lead them to shelters when unprepared owners find themselves unable to meet the breed’s demanding needs. For those ready for the commitment, adopting a rescued husky is an incredibly rewarding experience, offering a second chance to a deserving dog. This guide serves as your comprehensive starting point for connecting with reputable Siberian Husky rescue organizations dedicated to placing these intelligent, independent dogs in the right forever homes.

This resource is designed to eliminate the guesswork from your search. We will explore national databases like Petfinder and the AKC Rescue Network, alongside powerful regional-specific rescues such as Texas Husky Rescue and AZ Husky Rescue. For each organization listed, you will find a detailed breakdown of their unique approach. This includes critical information on their vetting processes for both dogs and adopters, typical adoption fees, the regions they serve, and what kind of post-adoption support you can expect. This clarity ensures you can find an organization that aligns with your specific needs and location.

Our goal is to provide a clear, actionable roadmap for everyone in the husky community, from prospective adopters and foster homes to volunteers and donors. We’ll also feature an in-depth look at the Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC), a specialized organization making a significant impact in the U.S. Southwest. Throughout the article, direct links are provided for every resource, empowering you to take the next step. Whether you’re actively looking to bring a husky home or simply want to support the cause, this curated directory will connect you with the best groups to make a real difference in a husky’s life.

1. Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC)

Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC) stands out as a premier organization for its deep specialization in arctic and northern breeds. Operating primarily in New Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, this volunteer-run nonprofit offers a comprehensive, welfare-focused approach that goes far beyond simple rehoming. Their process is built on a foundation of expert knowledge, ensuring each Siberian Husky, Malamute, or other northern breed is understood and placed in a home equipped for its unique needs.

For prospective adopters, this means a highly supportive and transparent experience. ADRTC’s commitment to thorough foster-home evaluation, full veterinary care, and precise family-dog matching instills confidence in the adoption process. It’s a standout choice among Siberian Husky rescue organizations for those who value specialized, breed-specific guidance.

Key Strengths and Features

ADRTC distinguishes itself through a robust support system designed for both the dogs and their new families. This holistic model is a significant advantage for anyone new to northern breeds.

- Breed Specialization: Their exclusive focus on arctic breeds, including rarer lines like Karelian Bear Dogs and Siberian Laikas, means every staff member and volunteer possesses deep, practical knowledge. This expertise directly informs their matching process, connecting dogs with owners who understand their temperament, exercise, and grooming needs.

- Comprehensive Care Protocol: Every dog receives a full health and behavioral assessment in a foster home setting. This includes spaying or neutering, vaccinations, and microchipping. This crucial step ensures dogs are healthy and well-adjusted before they are even listed for adoption.

- Post-Adoption Support: ADRTC offers an invaluable safety net for adopters. They provide breed-specific training services for obedience, leash manners, and crate training. A 14-day return guarantee offers peace of mind, ensuring that if a placement isn’t the right fit, the dog can safely return to the rescue.

- Transparent and Fair Adoption Process: Adoption fees are clearly stated, typically around $175 for older dogs and $225 for younger ones. As a volunteer-run organization, these fees directly support animal care rather than administrative overhead.

Practical Information for Adopters and Supporters

- Geographic Focus: The organization primarily serves New Mexico and the surrounding Southwest region. Out-of-state adoptions may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

- Typical Dogs: Most available dogs are between 1-3 years old, a common age for huskies to be surrendered when their high energy becomes a challenge for unprepared owners.

- How to Get Involved: Beyond adoption, ADRTC offers numerous ways to contribute. Their website details opportunities for fostering, volunteering, donating, and accessing educational resources through their blog.

Website: adrtc.org

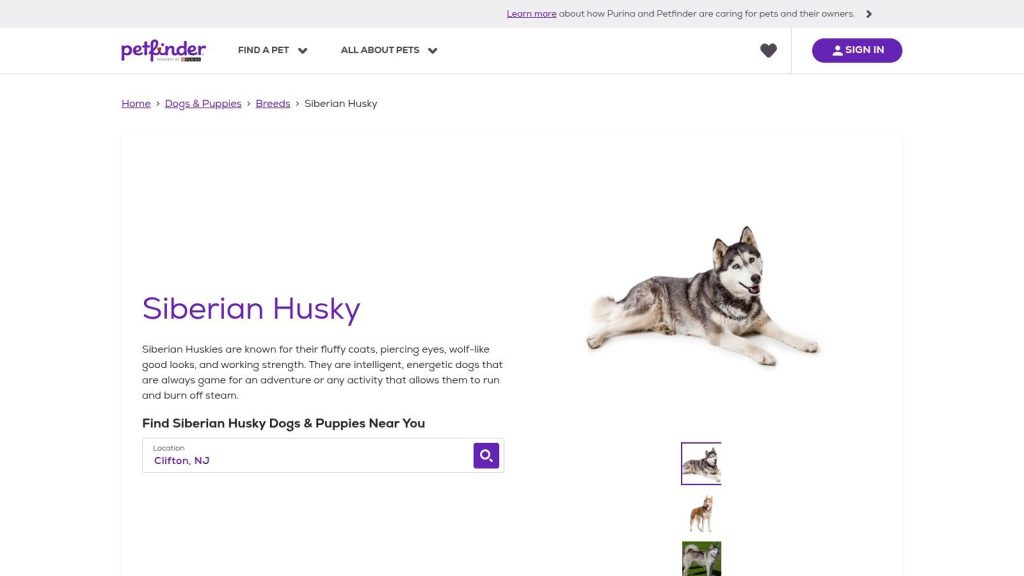

2. Petfinder – Siberian Husky breed page

Petfinder serves as a massive, nationwide database, aggregating real-time listings from thousands of shelters and rescue groups. Its dedicated Siberian Husky breed page is an excellent starting point for prospective adopters to survey the landscape of available dogs across the entire United States. The platform allows you to see which Siberian Husky rescue organizations have dogs near you and what types of dogs are currently in the system.

The user experience is straightforward, with powerful filters for location, age, and gender, making it easy to narrow your search. You can also save searches and receive email alerts for new Huskies that match your criteria. While browsing, you’ll find valuable breed-specific information, care guidance, and frequently asked questions directly on the page. Before diving in, it’s wise to review the breed’s unique needs; you can learn more about if a Siberian Husky is right for you to ensure you are fully prepared.

Platform Analysis

Petfinder’s primary strength is its sheer volume and reach, offering an unparalleled view of adoptable Huskies. However, its decentralized nature means that the quality of listings and the responsiveness of contact points can vary significantly between different partner organizations.

- Pros:

- Massive, searchable inventory with broad U.S. coverage.

- Easy to compare dogs from different rescues and shelters.

- Free to browse, with useful save and alert functions.

- Cons:

- Listings can become outdated as availability changes quickly.

- Adoption processes and communication standards vary by the listing organization.

Website: https://www.petfinder.com/dogs-and-puppies/breeds/siberian-husky

3. Adopt a Pet – national listings

As another major national adoption marketplace, Adopt a Pet provides a vast, searchable database connecting prospective adopters with shelters and rescue groups across the country. The platform is an excellent resource for finding Siberian Husky rescue organizations and individual dogs available for adoption, featuring robust search tools that allow you to quickly survey the landscape. Its user-friendly interface lets you filter by ZIP code, view dogs on a map, and see which organizations are active in your area.

The platform streamlines the initial stages of the adoption process by providing direct contact information for the listing organization, often including details like adoption fees and shelter hours directly on the dog’s profile. Users can create a profile, save searches, and set up alerts for new Huskies that become available. Once you find a potential match, you can start preparing for their arrival by creating a shopping list for your new dog to ensure you have everything you need.

Platform Analysis

Adopt a Pet’s key advantage lies in its detailed listings and the clarity it provides on the adoption process for each specific organization. While not exclusively for Huskies, its powerful filtering makes it a strong contender for anyone beginning their search.

- Pros:

- Broad U.S. coverage with frequently updated listings from many shelters.

- Clear “how to adopt” steps are often provided by each listing organization.

- Free to browse, with helpful search alert and favoriting features.

- Cons:

- Not Husky-specific, so users must refine their search to find the right breed.

- Some listings may be duplicated across other major adoption platforms.

Website: https://www.adoptapet.com

4. AKC Rescue Network – Siberian Husky rescue listings

The American Kennel Club (AKC) Rescue Network is not a direct adoption platform but rather a national directory connecting potential adopters with breed-specific rescue groups. Its Siberian Husky page acts as a trusted, centralized hub, listing contact information for dozens of dedicated Siberian Husky rescue organizations across the country. This resource is particularly valuable for verifying the legitimacy of a rescue, as many listed groups are affiliated with the Siberian Husky Club of America, the official AKC parent club.

The network provides a crucial layer of credibility and is an excellent starting point for research. Instead of browsing individual dog profiles, users find a state-by-state list of vetted organizations. From there, you can visit each group’s independent website to see available dogs and learn about their unique adoption or fostering processes. If you’re considering getting involved, many of these organizations are in dire need of support, and you can find out how to become a dog foster parent to make a significant impact.

Platform Analysis

The AKC Rescue Network’s main advantage is its authority and focus on connecting people with reputable, breed-experienced rescues. It’s less of a search engine and more of a high-quality phonebook for finding the right people to contact. The user experience is simple, directing you to the experts rather than having you sift through unverified listings.

- Pros:

- High trust and credibility due to AKC affiliation and parent club ties.

- Excellent resource for finding legitimate, breed-specific rescue groups.

- Provides direct contact information, cutting out a third-party platform.

- Cons:

- Functions only as a directory; it does not host live listings of adoptable dogs.

- Requires users to visit and apply through each rescue’s individual website.

Website: https://www.akc.org/akc-rescue-network/

5. Siberian Husky Club of America (SHCA) – Locating a Siberian Rescue

The Siberian Husky Club of America (SHCA) serves as the definitive authority on the breed, and its “Locating a Siberian Rescue” page is an essential resource for prospective adopters. Rather than listing individual dogs, this platform acts as a trusted directory, guiding users to a network of SHCA Trust-approved rescue organizations. This ensures that the groups you find are vetted and adhere to high standards of care and ethics.

The site provides more than just a list of links; it offers crucial context for anyone considering adoption. You can find valuable training and behavior resources tailored specifically to the unique challenges and characteristics of northern breeds. This educational approach helps prepare adopters for the realities of Husky ownership, setting both the dog and the new family up for success. It is an excellent starting point for finding reputable Siberian Husky rescue organizations in your region.

Platform Analysis

The SHCA’s primary value is its credibility. By starting your search here, you are accessing a curated list of rescue groups that meet the national breed club’s standards. However, the site is a referral hub, not a direct adoption portal, meaning you will need to continue your search on the individual rescue websites it recommends.

- Pros:

- Authoritative and credible referrals from the national breed club.

- Provides vital breed-specific training and behavior resources.

- Helps adopters connect with vetted and reputable rescue groups.

- Cons:

- Does not host listings of currently adoptable dogs.

- Requires users to navigate to external websites to find available Huskies.

Website: https://www.shca.org/locating-a-siberian-rescue

6. Rescue Me! – Siberian Husky network

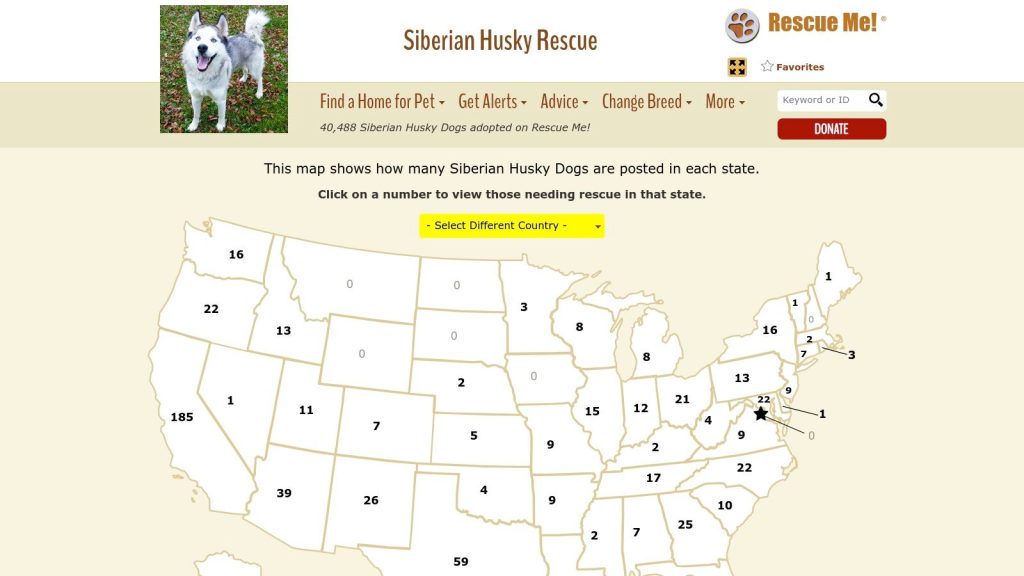

Rescue Me! is a long-standing online network that connects adoptable animals with new homes, and its Siberian Husky section provides a unique, state-focused directory. The platform is organized geographically, allowing users to click directly on a map of the United States to view available Huskies in their state. This approach offers a quick and straightforward way to survey local availability, often including dogs from smaller, independent rescuers or even owners needing to rehome their pets.

The interface is simple, prioritizing speed and accessibility over complex features. Each state page lists available dogs with photos and basic details, providing direct contact information for the poster. This direct line of communication can be beneficial for getting fast answers, but it also means that the experience and adoption process are entirely dependent on the individual or group listing the dog. Among the various siberian husky rescue organizations, Rescue Me! stands out for its geographical navigation and inclusion of harder-to-reach areas.

Platform Analysis

Rescue Me!’s key advantage is its granular, state-by-state organization, which is excellent for users who want to quickly check for Huskies in their immediate region without navigating complex search filters. The inclusion of owner surrenders provides another avenue for adoption, though it requires additional diligence from prospective adopters to vet the situation.

- Pros:

- Simple, map-based navigation for fast state-specific searches.

- Broad coverage that often includes smaller towns and rural areas.

- Direct contact with the lister, which can speed up the communication process.

- Cons:

- Listing quality and information can be inconsistent across different posters.

- Includes owner rehoming posts, which may not offer the same support as a formal rescue.

Website: https://husky.rescueme.org/

7. Adopt A Husky, Inc. (IL/WI)

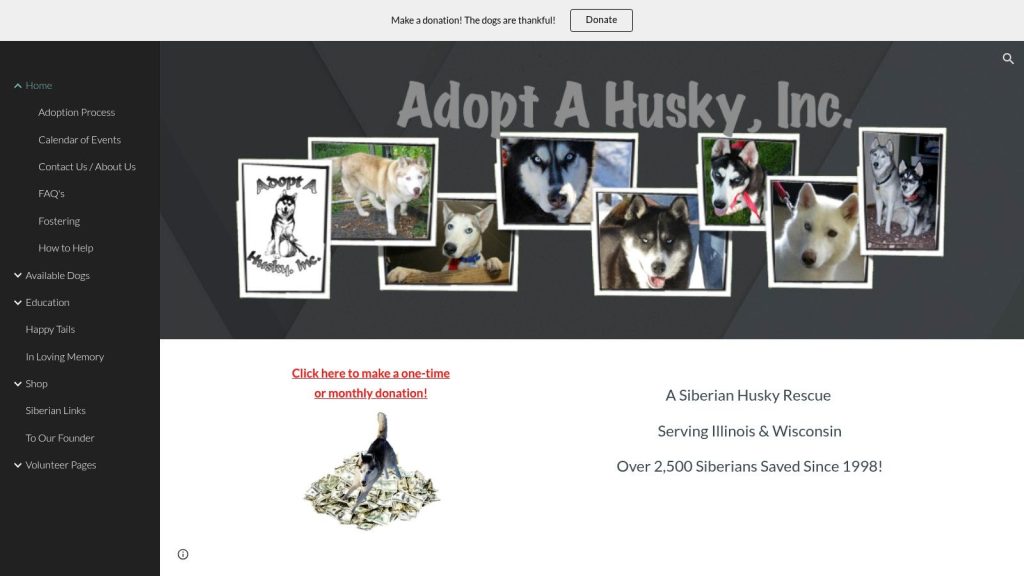

Adopt A Husky, Inc. is a dedicated, breed-specific rescue that has been serving Illinois and Wisconsin since 1998. This organization offers a focused and experienced approach, concentrating exclusively on the rehoming and welfare of Siberian Huskies. Their website provides a clear portal for prospective adopters to view available dogs, understand the group’s mission, and access educational resources pertinent to the breed.

The platform is straightforward, featuring profiles of adoptable Huskies and a clear pathway to submit an online adoption application. Beyond adoptions, the organization is active in the community, hosting events and offering opportunities for volunteering and donations to support their rescue efforts. Their long-standing presence makes them a trusted regional hub for anyone looking to connect with one of the most established Siberian Husky rescue organizations in the Midwest.

Platform Analysis

Adopt A Husky, Inc.’s primary advantage is its deep regional expertise and decades-long commitment to a single breed. This focus allows for a highly knowledgeable and supportive adoption experience. However, its services are geographically concentrated, which may be a limitation for those outside its immediate service area.

- Pros:

- Long track record (since 1998) and specialized regional Husky expertise.

- Transparent contact information and active community programs.

- Husky-only focus ensures deep understanding of the breed’s needs.

- Cons:

- Regional scope requires adopters to be within or travel to Illinois or Wisconsin.

- Specific adoption fee details may require an application or direct inquiry.

Website: https://www.adoptahusky.com/

8. Texas Husky Rescue

Texas Husky Rescue is a large, breed-specific nonprofit serving the entire state of Texas. It stands out as one of the most organized Siberian Husky rescue organizations due to its structured vetting process, extensive foster network, and transparent adoption fee schedule. The organization is dedicated to rescuing, rehabilitating, and rehoming Siberian Huskies and Husky mixes from high-kill shelters and situations of neglect or abuse across the state.

The website features detailed adoptable dog profiles, each providing insight into the dog’s personality, history, and specific needs. Prospective adopters can find an online application and educational resources that carefully outline breed-specific requirements, such as secure fencing and exercise needs, to ensure a successful match. The platform also offers clear pathways for getting involved through volunteering, fostering, or supporting the rescue by purchasing merchandise. This comprehensive approach makes it a valuable resource for anyone in the region looking to adopt.

Platform Analysis

Texas Husky Rescue’s key strength is its well-defined, transparent process that guides adopters from application to post-adoption support. Their emphasis on education and matching dogs to the right home environment is a cornerstone of their operation. However, its regional focus and specific policies may present limitations for some applicants.

- Pros:

- Transparent adoption fees and a clearly outlined adoption process.

- Statewide presence with an experienced foster network providing behavioral insights.

- Strong focus on educating adopters about the breed’s unique needs.

- Cons:

- Adoption priority is typically given to applicants within Texas and surrounding states.

- Adoption trial periods may include non-refundable fees if a dog is returned.

Website: https://texashuskyrescue.org/adoptables/

9. Free Spirit Siberian Rescue (huskyrescue.org)

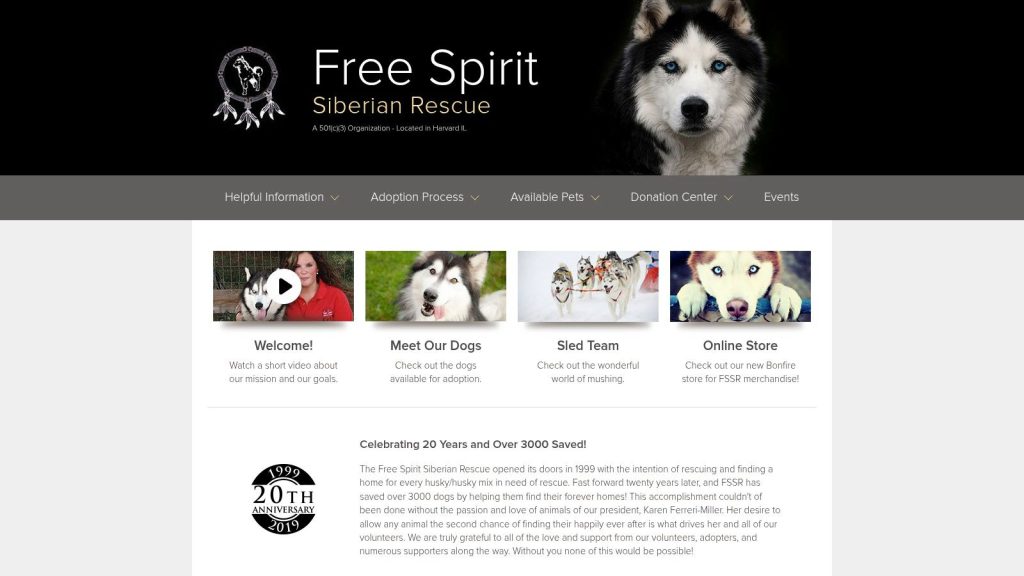

Based near Harvard, Illinois, Free Spirit Siberian Rescue is a highly respected organization serving the Midwest. With a mission focused exclusively on the Siberian Husky, they offer a well-organized platform for prospective adopters within their service area. Their website features a regularly updated catalog of adoptable dogs, each with a detailed profile, alongside a unique section for private-owner rehoming assistance.

The user experience is direct and informative, clearly outlining the adoption process and geographic limitations from the start. A standout feature is their defined adoption radius, which covers an approximate three-hour driving distance from their location. This policy ensures they can conduct thorough home visits and provide post-adoption support effectively. Their long-standing presence in the rescue community makes them a trustworthy resource for anyone looking for Siberian Husky rescue organizations in the region.

Platform Analysis

Free Spirit’s decades of experience are evident in their structured approach and deep understanding of the breed’s needs. Their hyper-local focus allows for a high standard of care and vetting for both dogs and adopters. However, this focused service area is a key limitation for those living outside the immediate Midwest.

- Pros:

- Extensive Husky experience with thousands of successful adoptions over decades.

- Transparent adoption geography and clear, step-by-step process.

- Offers a separate section for private-owner rehoming, a valuable community service.

- Cons:

- Strictly limited to a defined driving radius of about 3 hours from Harvard, IL.

- Adoption fees are not prominently listed on the initial application page.

Website: https://www.huskyrescue.org/

10. Husky House

Based in New Jersey, Husky House is a dedicated non-profit organization serving the tri-state area of New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. This group focuses on rescuing, rehabilitating, and rehoming Siberian Huskies and other northern breeds. A unique aspect of their operation is the “Snowdog Lodge,” a boarding and daycare facility that helps generate funds to directly support their extensive rescue activities, creating a sustainable model for animal welfare.

The website is a central hub for all their operations, featuring detailed profiles of adoptable dogs, an events calendar for meet-and-greets, and clear pathways for getting involved. Prospective adopters can find comprehensive applications, while supporters can discover opportunities to foster, volunteer, or donate through their wishlist. The organization also champions responsible pet ownership by supporting on-site spay and neuter programs. This makes it a key resource for those looking into Siberian Husky rescue organizations in the Northeast.

Platform Analysis

Husky House stands out due to its strong community presence and self-sustaining financial model. Their integrated approach, combining rescue with a public-facing business, ensures a steady stream of support for their mission. The application-first process ensures that potential adopters are serious and well-vetted before meeting a dog.

- Pros:

- Well-established rescue with a strong presence in the Northeast.

- Multiple ways to support the cause, including donations, volunteering, and using their boarding services.

- Sustainable funding model through their Snowdog Lodge business.

- Cons:

- Viewing adoptable dogs is often limited to events or post-application approval.

- The regional focus requires adopters to be within or willing to travel to the NJ/NY/PA area.

Website: https://www.huskyhouse.org/

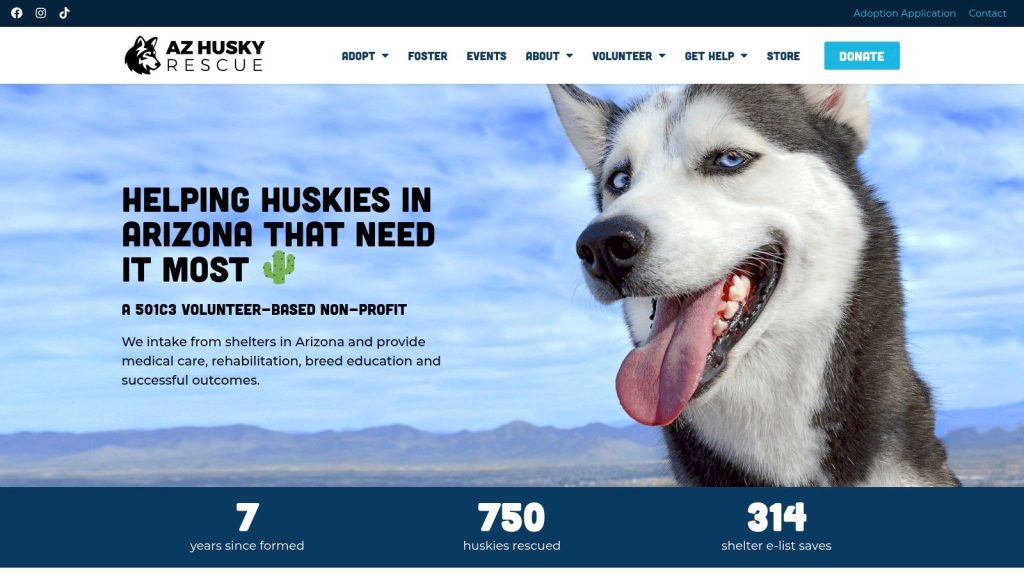

11. AZ Husky Rescue

AZ Husky Rescue is an Arizona-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to Siberian Huskies and similar northern breeds. This organization is a fantastic resource for potential adopters in the Southwest, particularly Arizona and neighboring areas like New Mexico. They maintain a clear ‘Available Huskies’ page on their website where you can view dogs in their care and submit an online adoption application directly.

A key feature is their schedule of regular adoption events, with specific dates and locations clearly listed, allowing prospective families to meet the dogs in person. The website also provides valuable resources for those needing to rehome a dog and general Husky care information. This transparent, community-focused approach makes them a standout among Siberian Husky rescue organizations in the region.

Platform Analysis

AZ Husky Rescue excels through its strong local presence and active community engagement. Their partnerships with local shelters ensure a steady intake of dogs in need, while their event schedule provides crucial in-person interaction for potential adopters. The focus is clearly on making successful, well-supported local placements.

- Pros:

- Strong local shelter intake partnerships and an active event schedule.

- Transparent communications and helpful resources for new and existing owners.

- Simple online application process integrated with available dog profiles.

- Cons:

- Geographic priority is given to Arizona residents, limiting options for out-of-state adopters.

- Adoption fees and specific requirements are provided during the screening process rather than being publicly listed.

Website: https://azhuskyrescue.com/

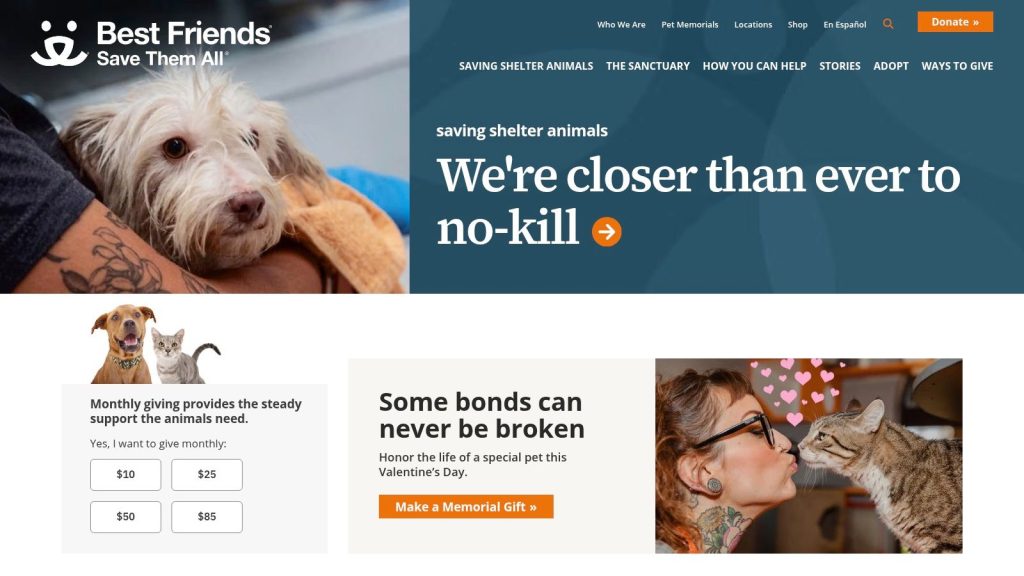

12. Best Friends Animal Society – adoptable Husky listings

Best Friends Animal Society is a leading national animal welfare organization with a mission to end the killing of dogs and cats in America’s shelters. Their website features a searchable database of adoptable dogs, including those at their own lifesaving centers and through their extensive network of partner rescues. For those looking for Siberian Husky rescue organizations, the platform serves as a high-quality resource to find available dogs from reputable sources.

To find a Husky, users can apply the “breed” filter on the adoption search page. Each listing provides key details like age, location, and specific instructions for visiting or applying. The platform stands out due to the high operational standards and transparency upheld by Best Friends and its affiliates, ensuring that the dogs listed are well-cared for. This offers a level of trust and reliability that can be reassuring for first-time adopters.

Platform Analysis

The main advantage of using Best Friends is its commitment to no-kill principles and the high standards it promotes across its national network. While not a Husky-specific rescue, its powerful search tools make it easy to locate the breed within a network of trusted organizations. The user interface is clean and straightforward, focusing on connecting adopters with their new companions efficiently.

- Pros:

- High operational standards and transparency across its centers and network.

- Multiple adoption locations and a large national partner network.

- Strong focus on animal welfare and no-kill advocacy.

- Cons:

- Not Husky-exclusive; requires using filters to locate the breed.

- Some listed dogs may be mixes or located outside your immediate region.

Website: https://bestfriends.org/adopt

Siberian Husky Rescue Organizations — 12-Point Comparison

| Organization | Core features | Trust / Quality ★ | Value & Fees 💰 | Target & USP 👥 / ✨ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🏆 Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC) | Breed-specialized (Husky, Samoyed, Malamute, rare northerns), foster evaluations, spay/neuter & vaccines, obedience/leash/crate training, 14-day return | ★★★★★ | 💰 $175–$225, nonprofit/transparent | 👥 Breed-focused adopters, fosters & volunteers; ✨ expert matching & post-adopt support |

| Petfinder – Siberian Husky page | Nationwide live listings, ZIP/age/sex filters, alerts, direct contact to rescues | ★★★★☆ | 💰 Free to browse; fees vary by listing | 👥 Nationwide seekers; ✨ real-time large inventory |

| Adopt a Pet – national listings | Map/ZIP filters, org pages with adoption steps, listing fee info, alerts | ★★★★ | 💰 Free to browse; fees shown per org | 👥 General adopters comparing regions; ✨ clear adoption process guidance |

| AKC Rescue Network – Siberian listings | Breed-organized directory, contact details, links to club-affiliated rescues | ★★★★★ | 💰 Directory free; adoption fees set by individual rescues | 👥 Owners seeking vetted breed clubs; ✨ AKC-backed credibility |

| Siberian Husky Club of America (SHCA) | Locating a Siberian Rescue guide, SHCA Trust referrals, training & behavior resources | ★★★★☆ | 💰 Free guidance; adoption fees via referrals | 👥 Prospective Husky owners & surrenderers; ✨ authoritative breed resources |

| Rescue Me! – Siberian network | State-by-state listings, U.S. map navigation, alerts & success stories | ★★★ | 💰 Free; varied poster sources | 👥 Searchers in smaller/remote areas; ✨ broad state coverage |

| Adopt A Husky, Inc. (IL/WI) | Husky-only adoptables, online application, events, education | ★★★★ | 💰 Regional fees (inquire) | 👥 IL/WI adopters; ✨ long regional experience since 1998 |

| Texas Husky Rescue | Detailed adoptables, online app, education, foster network, merchandise support | ★★★★ | 💰 Transparent fees; statewide focus | 👥 Texas & nearby adopters; ✨ strong counseling & foster support |

| Free Spirit Siberian Rescue | ‘Available Dogs’ gallery, private-owner rehoming, defined adoption radius | ★★★★ | 💰 Fees not always posted publicly | 👥 Midwest adopters within driving radius; ✨ decades of Husky experience |

| Husky House | Application-based adoptions, foster/volunteer programs, Snowdog Lodge boarding (fundraiser) | ★★★★ | 💰 Fees/process via application | 👥 NJ/NY/PA adopters & supporters; ✨ boarding funds rescue work |

| AZ Husky Rescue | ‘Available Huskies’ page, regular adoption events, rehoming resources | ★★★★ | 💰 Fees discussed during screening; regional priority | 👥 Arizona / Southwest adopters; ✨ active events & shelter partnerships |

| Best Friends Animal Society – adoptable Husky listings | Searchable adoptable DB, center listings, national partner network, no-kill advocacy | ★★★★★ | 💰 Free to search; partner adoption fees vary | 👥 Nationwide adopters seeking reputable centers; ✨ high operational standards |

Finding Your Pack: How to Choose the Right Rescue and Take the Next Step

Navigating the world of animal rescue can feel as vast and complex as a Siberian wilderness, but this guide has equipped you with a map and a compass. We’ve explored a comprehensive landscape of national search platforms, breed-specific networks, and dedicated regional groups. Each of these Siberian Husky rescue organizations offers a unique pathway to bringing one of these magnificent dogs into your life.

The key takeaway is that there is no single “best” rescue; the right choice is deeply personal and depends entirely on your individual circumstances. Your journey is now about moving from research to action, armed with the knowledge of how to match your needs with the right organization.

Synthesizing Your Options: From Broad Searches to Specialized Support

Let’s distill the primary pathways you’ve discovered. For prospective adopters who are just beginning their search or live in areas without a dedicated regional rescue, the large aggregators are your ideal starting point. Platforms like Petfinder and Adopt a Pet cast the widest possible net, allowing you to survey available huskies from hundreds of shelters and rescues at once. Similarly, the AKC Rescue Network and the Siberian Husky Club of America (SHCA) provide trusted, breed-specific directories that can point you toward reputable operations in your state.

However, for those seeking a more hands-on, deeply supported experience, a specialized, regional rescue is unparalleled. Organizations like Texas Husky Rescue, AZ Husky Rescue, and our featured group, Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC), offer more than just a dog. They provide a community, breed-specific behavioral assessments, and often, crucial post-adoption training resources. This level of support is invaluable, especially for first-time husky owners or those adopting a dog with a known history of behavioral challenges. These rescues invest heavily in rehabilitation, ensuring the dogs are not just saved, but are set up for lifelong success in their new homes.

Your Action Plan: How to Take the Next Step

Your next move is to engage directly. Don’t just browse; begin the application process with one or two organizations that align with your goals. Here are the critical steps to follow:

- Honesty and Detail are Non-Negotiable: When you fill out an application, be completely transparent. Describe your home, your family’s activity level, your work schedule, and your experience with dogs, especially with northern breeds. Rescues aren’t looking for a “perfect” home; they are looking for the right home for a specific dog’s needs.

- Prepare for the Process: Understand that rescue is not an instant transaction. It involves applications, reference checks, interviews, and often, home visits. This thorough process exists for one reason: to protect the dogs and ensure they are placed in safe, permanent homes. Patience is a virtue that will be rewarded.

- Look Beyond Adoption: If now isn’t the right time to adopt, consider other vital roles. Fostering is one of the most impactful ways you can help, as it directly frees up space for another dog to be saved. Volunteering your time or providing a donation are also critical contributions that keep these life-saving operations running.

Choosing to bring a rescued husky into your life is a significant commitment, but it is one that offers profound rewards. These intelligent, adventurous, and deeply loving dogs have so much to give. By working with the dedicated Siberian Husky rescue organizations featured here, you are not just finding a pet; you are saving a life and gaining a loyal companion for all the adventures that lie ahead.

Ready to take the first step with an organization that specializes in both rescue and rehabilitation? For those in the Southwest, the Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC) offers unparalleled breed expertise and post-adoption support to ensure a successful transition for both you and your new companion. Explore their adoptable dogs and learn more about their unique training programs at Arctic Dog Rescue and Training Center (ADRTC).